Om sweet Om: (high-)functional frontend engineering with ClojureScript and React

We’re firm believers that great products come from a marriage of thoughtful design with rigorous engineering. Effective design requires making educated guesses about what works, building out solutions to test these hypotheses quickly, and iterating based on the results. For example, if you’ve read about our recent feed redesign, then you know that we tested three very different feed layouts in the past year before landing on a design that we and most of our users are quite happy with.

Constant experimentation and iteration presents us with an interesting technical challenge: creating a frontend architecture that allows us to build and test designs quickly, while maintaining acceptable performance for our users.

Specifically, (like most software engineering teams) our primary engineering goals are to maximize productivity and team participation by writing code that:

- is modular, with minimal coupling between independent components;

- is simple and readable; and

- has as few bugs as possible.

In our experience developing web, iOS, and backend applications, we’ve found that much (if not most) coupling, complexity, and bugs are a direct result of managing changes to application state. With ClojureScript and Om (a ClojureScript interface to React), we’ve finally found an architecture that shoulders most of this burden for us on the web. Two months ago, we rewrote our webapp in this architecture, and it’s been a huge boost to our productivity while maintaining snappy runtime performance.

This new codebase weighs in at just under 5k lines of ClojureScript (excluding libraries), about five times smaller than our previous ClojureScript codebase. Of course, size isn’t everything. Every member of our backend team has made significant contributions to the new codebase, which says a lot about its readability and accessibility.

Read on for more details about how we’ve been iterating faster with ClojureScript, React, and Om.

ClojureScript

Our backend is built with Clojure, a beautifully-designed, modern Lisp dialect running on the JVM, which we find to be an incredibly powerful language for real-world software engineering. Clojure has excellent support for functional, data-oriented programming with efficient immutable data structures at its core. It is also highly expressive, supporting powerful fine-grained, composable abstractions, and nearly infinite extensibility via tasteful use of macros.

Given our love of Clojure, we were ecstatic about the introduction of ClojureScript, a Clojure dialect that compiles to JavaScript, and brings the benefits of Clojure to the web. ClojureScript also achieves the same high performance as Clojure by relying on modern JavaScript engines coupled with the excellent Google Closure library.

Functional Programming

Functional programming encourages writing pure functions that are free of side-effects and always return the same value for a fixed set of explicit inputs. Knowing that a function is free of side-effects and global references gives a programmer the peace-of-mind to call a function and know that it is only computing the result and doing nothing else. Pure functions are modular by definition, making them easier to reason about, test, and compose into more complex functions.

In ClojureScript, all values are immutable by default. Moreover, ClojureScript comes with efficient implementations of persistent immutable maps, vectors, and lists baked in. You can’t change these persistent data structures; instead, “modifications” return new, updated data structures, while retaining reasonable performance via structural sharing. These design choices make writing pure functions a breeze, ensuring that you don’t have to worry about clients mutating your precious data without your consent, while leaving the door open for explicit mutable references when they are the pragmatic choice.

Macros

ClojureScript also includes a powerful macro system, which enables language extensions at the library level that would be impossible in most other programming languages. A ClojureScript macro is a Clojure function that is executed at compile-time, and can use the full power of the Clojure language to build new code from its unevaluated arguments. This powerful yet simple code-generation ability makes it easy to abstract away most boilerplate, add new syntax to the language, or optimize generated code for size and client-side performance.

For example, ClojureScript’s “thread-last” macro ->> turns a nested form inside-out, making it more readable as a pipeline of manipulations. Given its usefulness and general applicability, the implementation of the macro can be quite short:

As a use case, take the following highly nested form that applies a set of transformations on a vector of numbers: filtering to only include the odd values, taking the first two, getting the last element of the truncated sequence, and then incrementing the result.

The threading macro allows us to write this sequence of operations in a more readable form that matches the way we think about it:

Another, more sophisticated example is core.async, a library that uses macros to bring goroutines and channels (in the spirit of Google’s Go programming language) to ClojureScript. Goroutines are a very natural way to express asynchronous communication patterns – which tend to arise frequently in web development – in a synchronous style (as straight-line code, without callbacks). Typically, support for this programming style must be baked into the compiler of a programming language,

but macros effectively allow you to extend the language so goroutines can be provided a’la carte as a lightweight library. We’ve also created a number of our own libraries that use macros to add new syntax to ClojureScript, including Plumbing, Schema, and om-tools.

React

While ClojureScript brings functional programming paradigms to the data side of the web, React brings them to the DOM, providing a simple and powerful framework for building composable user interfaces. If you aren’t yet familiar, we highly recommend Facebook’s post on why they built React. React’s documentation summarizes its core promise well: “Simply express how your app should look at any given point in time, and React will automatically manage all UI updates when your underlying data changes.”

Consistency of Data and the DOM

A common pitfall of web development is the often complicated interplay between the DOM and the data it displays. When a piece of data changes, all of its representations must be updated appropriately to maintain consistency. Any constraint that must be explicitly enforced by writing code leaves open the opportunity for a bug, and most web applications are thus riddled with such consistency constraints.

In a naive solution to this problem, each component that can update a piece of data must know about each other component concerned with this data, resulting in the following architecture that scales quadratically with the number of components:

A less error-prone solution is a hub-and-spoke architecture that maintains a single canonical representation of each piece of state, and all components that modify or represent this state communicate directly with the central hub:

This hub-and-spoke architecture reduces the number of constraints to linear in the number of components. Two-way template binding, the latest Right Way To Do Things, provides abstractions that reduce the boilerplate needed to implement this approach. But, as React developer Pete Hunt argues, it hasn’t done so very well. Since two-way template binding is a difficult problem to get right, each library invents its own ecosystem around the templating system, which is nearly impossible to extend and maintain long-term.

React proposes a simple solution to this “state problem” that might seem crazy at the outset. You just write pure JavaScript functions that translate your data into a virtual representation of the DOM. React calls these functions once to generate the DOM for each component when your application loads. Then, each time the data driving a component changes, React automatically calls the corresponding function again to regenerate the affected parts of the UI. Conceptually, that’s all there is to it – the UI is just a functional projection of your application state.

This probably sounds like a performance nightmare. But by maintaining a virtual DOM, React can efficiently compare what is currently shown on screen to what should be shown while avoiding slow queries to the real DOM. React then computes and executes the smallest set of possible changes to transform the current DOM to match the new virtual DOM. Because DOM manipulation is far slower than JavaScript calculations, the overall performance of React often matches (or even exceeds) that of other common approaches, while freeing the programmer from reasoning about maintaining consistency between components and what needs to be updated as the result of a data change. All the incidental complexity that naturally arises from mutation of the DOM melts away.

Om

The core design philosophy behind React is inherently functional, and in many ways it fits more naturally with a functional language like ClojureScript than JavaScript. Om builds on React, taking its ideas even further by using ClojureScript’s immutable data structures to represent application state, enabling further architectural and performance benefits.

Single, Normalized Application State

Good functional style avoids mutation when practical. But, interactive interfaces are by definition constantly changing from one state to another in response to user input. In this case, the maximally functional solution is to push mutation to the edges of the system, by means of a single mutable reference that points to an immutable data structure that represents the entire application state in a normalized format.

There are several important benefits to this approach.

First, there is a single mutable reference that points to the global application state. Localizing mutation to a single place minimizes cognitive complexity, making the application much easier to reason about.

Second, the state is all collected into a single immutable object. Since at the end of the day the state is what drives the entire application, this makes it maximally transparent to engineers working in the codebase. If you understand the state, then you understand the core of the entire application; the rest is “just” logic for displaying and updating the state. A single state also has other interesting benefits like providing application-wide snapshotting and undo for free.

Finally, the state is normalized: each piece of information is represented in a single place. Since React ensures consistency between the DOM and the application data, the programmer can focus on ensuring that the state properly stays up to date in response to user input. If the application state is normalized, then this consistency is guaranteed by definition, completely avoiding the possibility of an entire class of common bugs.

However, there are several potential issues with using a single application state.

First, it seems to contradict our functional ideals of encapsulation, modularity, and compositionality. Ideally, we would like each component to have access to only the precise subset of data it needs, and be able to respond to user interactions by modifying the relevant data as necessary in a context-free manner, without needing to understand the structure of the entire global application state.

Second, React’s snappy performance relies to some degree on the modularity of components and their data: when data changes, only the components that care about this data are re-rendered. Collecting all the application state in one place seems like it would destroy this locality, requiring a (virtual) re-rendering of the entire app regardless of how small the data change.

Om provides solutions to these problems.

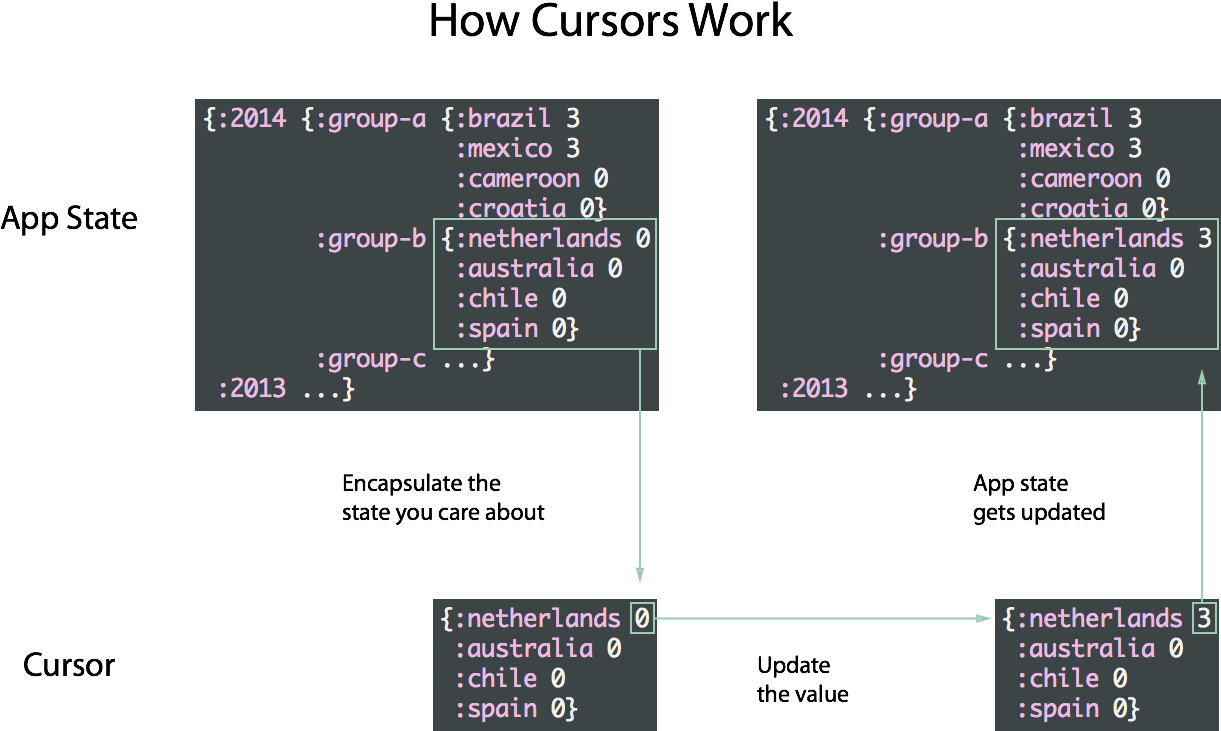

Om restores encapsulation and modularity using cursors. Cursors provide update-able windows into particular portions of the application state (much like zippers), enabling components to take references to only the relevant portions of the global state, and update them in a context-free manner.

To address the performance issue, Om leverages the power of ClojureScript and its persistent data structures. Because the same immutable data structure always represents the same data, it’s very efficient to tell which parts of the global state have changed between render cycles using reference equality checks. Om uses this ability to quickly identify the components that are possibly affected by a state change, and avoid invoking the virtual DOM diffing of React entirely for components that are unaffected.

An Example

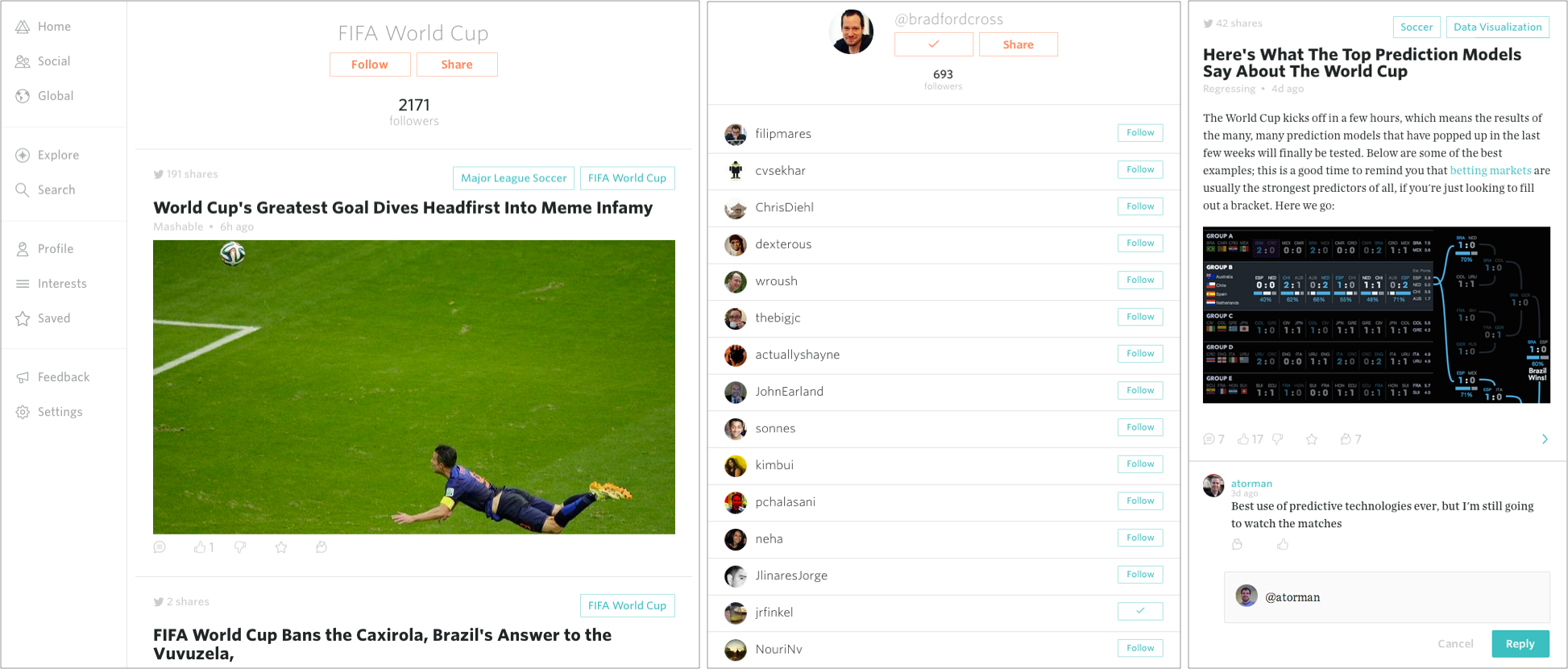

Users come to our site to find and share content relevant to their interests. They find this content in feeds, which are ordered collections of stories, each of which is automatically tagged with a set of relevant topics. Users can follow a topic to indicate their interest, and see more stories about it later.

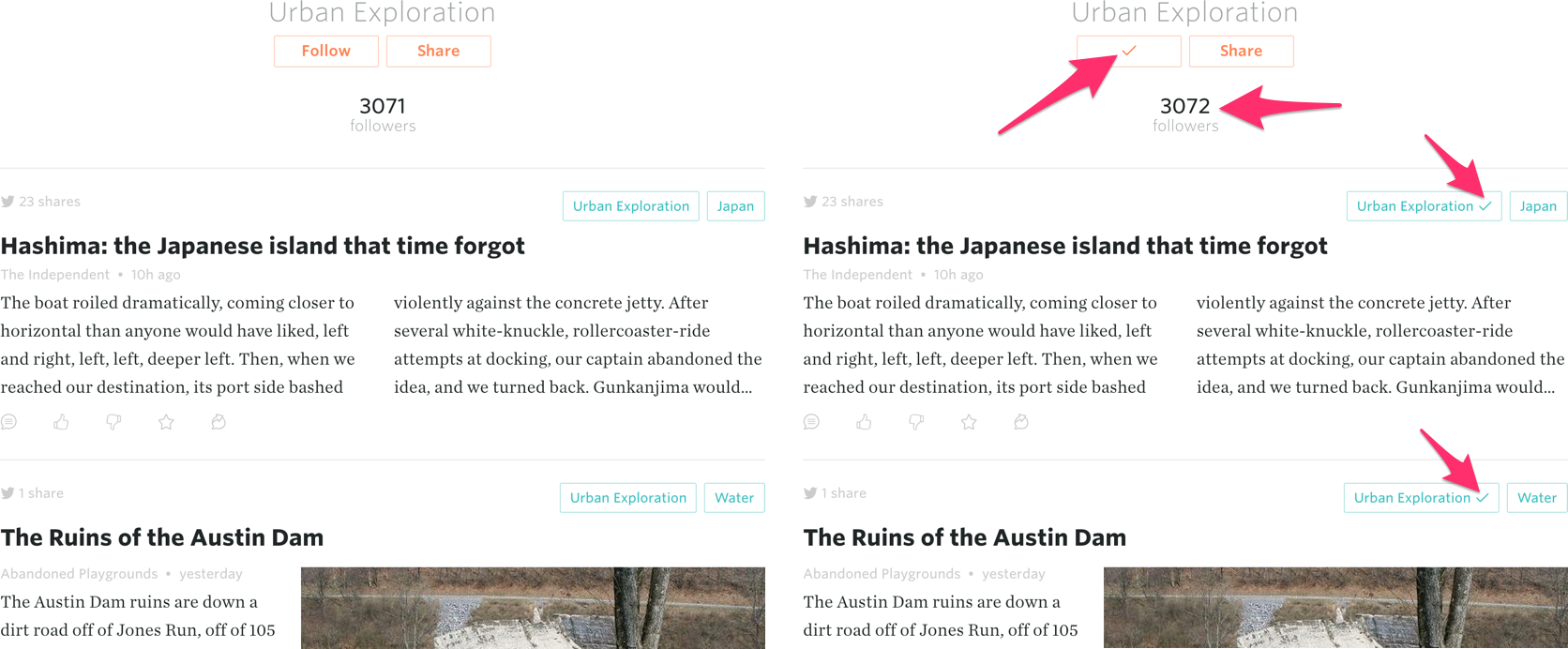

In the steady state, this is simple to implement. The backend sends down the list of topics that the user follows, and these are used to populate an interest list in the UI, as well as place a checkmark next to each followed topic tag on a story. For example, here is an image from the Urban Exploration feed. On the left is the view that the user sees if they are not following the Urban Exploration topic. When the user clicks on the “Follow” button under the feed header, however, this change must be propagated to the server, local state, and several places in the UI (highlighted with magenta arrows).

In general, a user can follow or unfollow a topic from several components, and the updated state must be reflected in all the other components. Managing this complexity with Om is simple: each component receives a cursor to a canonical repository of topic follow information derived from the global state, and projects this information to the UI and/or modifies it as necessary. Crucially, the component doing the modification doesn’t need to know or care about about this process, but only concerns itself with its own encapsulated reference into the relevant parts of the global application state provided by cursors.

Conclusion

We’ve found that together ClojureScript, React, and Om provide a simple way to manage data that changes over time, one of the most difficult problems in UI development. All user interactions and backend communication bubbles up to our single application state, which is decomposed into functional components that Om/React renders automatically. Om automatically manages keeping the representation of data consistent across independent components and allows us to focus on the underlying logic governing our application.

This stack enables us to use functional programming concepts to write code that is simpler, shorter, and easier to test and maintain. Since all the inputs and outputs for a single view are completely encapsulated in a single function, new engineers can easily edit a component without knowing anything else about the rest of the app, which has allowed our entire team to pitch in and contribute changes with very little ramp-up cost.

Thanks to: Scott Rabin, Kevin Lynagh, and Sean Grove and for reading drafts of this

This post has just scratched the surface of what’s possible; subscribe to be notified of follow-up posts, including more details of how to use Om, share code between client and server with cljx, generate responsive CSS using Garden, and more.