Prismatic's "Graph" at Strange Loop

At last month’s Strange Loop conference, I gave a talk about “Graph”, a library developed to simplify some of our complex software systems. This post will briefly summarize the main ideas behind Graph; if you’re left wanting more, the talk slides go into considerably more detail, including real-world examples, and we’ll be answering questions in the Hacker News thread.

Motivation

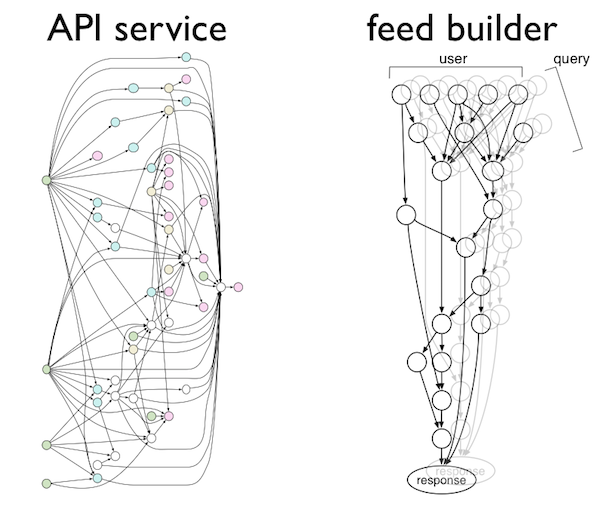

Software engineering is very important to us. We’ve written about our fondness for fine-grained, composable abstractions (FCAs). However, in a number of our real systems, we’ve relentessly refactored and modularized according to these principles, but still found ourselves left with complex top-level compositions like these:

At left is our production API service, and at right is our real-time newsfeed builder pipeline. As you can see, both are large networks of many components connected in complex webs of dependencies.

To keep ourselves happy and sane, we need a way to cleanly implement complex systems such as these. Moreover, we also want to reuse sub-systems across our code base, test our systems by mocking out components, and run our systems in production while monitoring each component for performance and failures.

A simple example

Before Graph, our implementations of each of the above systems consisted of a single monolithic function, with a large ‘let’ statement introducing a single node variable in each binding. This approach is simple, and satisfies the requirement that each node value is computed exactly once (regardless of how many children it has). Beyond that, however, there are a number of drawbacks to this ‘monster-let’ approach.

As a running example, consider the following function that returns a map of some simple univariate statistics of an input sequence of xs:

So, what’s wrong with this implementation?

Well, suppose that sometimes we only need to know the mean of our sample, other times we want just the mean-and mean-square, and sometimes we need everything. In all but the last case, calling stats is wasteful since it computes extra unneeded statistics. On the other hand, if we attempted to break stats apart into separate functions for each statistic, we’d waste effort re-computing :m and :m2 when we want it all (or end up with an ugly API where, e.g., variance expects partial results).

Or, suppose that we want to monitor the individual sub-computations in this function to see how much time each takes in production. We would have to individually instrument each computation with a time measurement, which is both verbose and error-prone.

(These criticisms may seem silly in the context of this simple example. Check out the slides for more about our real systems, which have similar issues but include dozens of components, polymorphism, and other complicating requirements.)

The basic point is that using large let statements to describe complex compositions can lead to verbose code that is brittle and difficult to debug, test and monitor. The core issue is that while as programmers we can see the individual components and their relationships, the rest of our code and tooling does not have access to this information because it is locked up inside an opaque function.

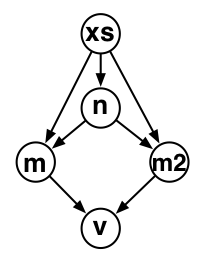

For example, this graph shows the nodes and data flow in our stats function, which is invisible from the outside (i.e., without examining the source code). Graph is about making this structure explicit.

What is Graph?

Graph is a simple, declarative abstraction to express compositional structure.

Declarative means that we should explicitly list a system’s components and dependencies in a way that is accessible to our tooling. This solves the issues of the previous section, enabling abstractions over a system’s components as well as reasoning about the composition as a whole. Of course, this idea is not new; for example, it is the basis of graph computation frameworks like Pregel, Dryad, and Storm, and existing libraries for system composition such as react.

Our primary objective in Graph is to distill this idea to its simplest, most idiomatic expression in Clojure, our language of choice. Concretely, a Graph is just a Clojure map of functions that can depend on the outputs of other functions. Because Graphs are just ordinary data, we can manipulate them for free using our favorite existing tools, making Graphs trivially easy to create, modify, run, reason about, test, and build upon. Put simply, Graph is an [FCA][swe] for composition.

It is better to have 100 functions operate on one data structure than 10 functions on 10 data structures. - Alan Perlis

As a first attempt in this direction, we could rewrite our stats example as a Clojure map, turning let variables into keywords and wrapping each of the corresponding value expressions in anonymous functions.

This gets us 90% of the way there. The individual components of the computation are now explicit, but the dependency information is still missing. For instance, there’s no way for our tools to know that the m in the arguments to the :v function refers to the mean computed in the second step of the graph – after compilation, it’s just the first argument to an anonymous function.

A brief digression: keyword functions

To bridge this gap, we introduce keyword functions. A keyword function (written defnk or fnk rather than defn or fn) is just a function that take a map as input, and pulls its arguments out from this map under the keywords with the same names:

As you can see, keyword functions are very similar to {:keys []} destructuring in an ordinary function’s argument list. Functionally, the main differences are a slightly cleaner syntax (especially for optional arguments), and assertions that all required keys are present in the input map. These are enough of a win that we find uses for fnk throughout our codebase.

For the purposes of Graph, however, the main advantage of fnks is that they are automatically assigned metadata specifying which keys are required and optional. You can easily examine the metadata of a compiled fnk and see which keywords it requires or expects in its input map.

Graph

With this addition, we can now formally define a Graph: a Graph is just a map from keywords to fnks. The required keys of each fnk specify the node relationships: each required key refers to the output of a previous node function under the same name, or if no such node is present, the value associated with this keyword in the input map. Here is the final Graph for the running example (we’ve just added a k to each fn).

The entire Graph itself specifies a fnk from input parameters to a map of results, just like the example written explicitly with defn and let above. Note, however, that the graph itself just describes the compositional structure of the computation, but says nothing about the actual execution strategy – more on this below.

Simple Compilation

The simplest thing we can do with a Graph is compile it to an ordinary function (fnk) that takes a map of inputs, and computes a map of outputs.

Calling graph/eager-compile on stats-graph produces a function that’s functionally equivalent to the initial explicit version, and (arguably) a bit cleaner and clearer. And, both the compilation process and the resulting function are strictly error-checked, so we can’t compile a cyclic graph or execute a compiled graph on an input map with missing arguments.

Advantages

Simpler code

While it may seem like a wash for our trivial ‘stats’ example, in some our real services Graph has lead to dramatically simpler, more compositional code.

For example, our feed builder system constructs personally ranked newsfeeds in real time, through a series of about 20 steps from query to response. One of the trickiest aspects of this system is that we offer more than 10 different types of feeds (home, social, global, topic, …), and each of these types requires a slightly different set of steps, dependency relationships, and parameters. When the feed builder was written as a single monolithic function, we struggled to cleanly represent this polymorphism using case statements, multimethods, or protocols. But once we expressed the core composition structure using Graph, the polymorphism became trivial – each feed just provides a set of nodes that are combined into a shared default Graph using ‘merge’.

Flexible execution strategies

The eager compilation presented above is just the simplest possibility; because the Graph is not tied to a single execution strategy, you can also compile graphs in more interesting ways:

For one, you can compile a Graph to a lazy map, so that values are only computed as needed. This solves the problem mentioned above: if you only need the mean, only the mean (and count) are computed, and if you need everything you get it all with only minimal overhead (each value is only computed once).

Similarly, you can automatically parallelize a Graph’s computations with parallel-compile, which executes independent steps concurrently. For instance, when computing the variance the mean and mean-square can be computed in parallel because there is no edge between them.

With a bit more tooling, we also compile Graphs to entire production services (where nodes build resources such as database handles and in-memory caches); and one could also compile Graphs to more exotic configurations such as cross-machine streaming topologies.

Monitoring, debugging, and testing

If the only benefit from Graph was simpler, more flexible and modular code, we’d be happy to stop there. But Graph also makes it much easier to debug, test, and monitor our production code.

For example, it’s trivial to write a higher-order function that takes a Graph and produces a new Graph that monitors the call counts and average execution times of each of the nodes:

We use this pattern to keep tabs on our Graphs running in production, and generate informative tables like this one on our internal dashboard:

For production services, similar patterns enable us to cleanly shutdown an entire service (flushing caches, destroying thread pools, and so on), and cleanly test entire services by mocking out nodes with merge/assoc as discussed above.

What’s next?

This post has just scratched the surface of what’s possible by using a simple, declarative abstraction like Graph to express the compositional structure of real software systems.

At the end of the Strange Loop talk, I mentioned the possibility of open sourcing Graph, and received an unexpectedly very positive response. We’re really excited about this possibility, and hope to make an alpha version available in the coming weeks. We’ve also developed many other libraries here that we’re excited about releasing to the community, so stay tuned!

Please let us know what you think in the Hacker News comments.