Graph: Abstractions for Structured Computation

We’ll be live on the discussion thread over on Hacker News.

To a first approximation, progress in technology is limited by the difficulties that engineers encounter in building, maintaining, and extending software that represents complex systems. For instance, Object-oriented programming encourages the decomposition of large systems into objects that encapsulate their state, making it easier to build, test, and reason about these systems. OOP was a massive step forward in software engineering, and today nearly all large-scale software endeavors (video games, search engines, etc.) are built within this paradigm.

The reason for this shift is that the older generation of procedural code with no state boundaries came with a complexity overhead that made it harder to understand the code than the actual concepts being represented. No software abstraction can reduce the inherent complexity of a problem, but it can reduce the complexity overhead, making it possible for engineers to build complex systems faster and with fewer bugs.

Functional Programming: where’d my structure go?

Unfortunately, OOP doesn’t inherently solve the flaws of procedural programming; it merely sweeps and bounds them under many small rugs. Within the boundaries of an object, OOP code tends to fall back to old procedural habits.

More recently, functional programming (FP) has received much attention as a more radical shift in software design. The core idea of FP is that good code should be organized around pure functions that take data and transform it, without modifying any shared state. Truly learning this lesson and having it influence the code you write ultimately implies re-training the core of how you think about software engineering.

Once an engineer comes to grok FP, they tend to organize code around how data ‘flows’ between these pure functions to produce output data. The structure of how functions connect to form the structure of a functional computation has typically been informal. Until now.

Introducing Graph

Last week, we open-sourced Graph as part of our plumbing library. Graph is a very simple, declarative way to describe how data flows between functions in an FP program. It allows us to formalize the informal structure of good FP code, and enables higher-order abstractions over these structures that can help stamp out many persistent forms of complexity overhead.

Concretely, a Graph represents the structured composition of any number of functions, using a Clojure map. Each entry in a Graph is a mapping from a node name (keyword) to a keyword function, which computes the value of its node from the values of other nodes and inputs from outside the Graph. The plumbing readme provides some simple examples of what Graph can do, and this test goes into more gory details on how to use Graph.

In this post, we want to focus more on how Graph can be used to reduce complexity overhead in large, real-world, FP systems, and thus allow us to design simpler and more maintainable code with less work. First, however, we want to say a few words about what Graph is not.

-

Graph is not for all function compositions. If you just want to compose functions

fandgand go on with your day, nothing is simpler (or more appropriate than)(comp f g). Instead, Graph is about removing the complexity overhead often encountered in large FP systems. -

Graph is not a distributed computation framework. In fact, it says nothing at all about how or where the node functions should be executed, but just describes how data flows from one function to another. This is actually a strength – as we will see, the ability to compose a Graph with various execution strategies helps us reduce complexity overhead – and distributed computation strategies are just one option that we will pursue in future releases.

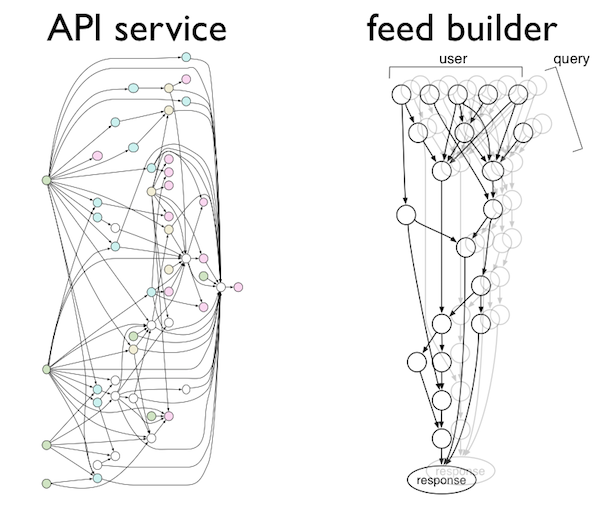

Jason Wolfe’s Strange Loop talk, slides and subsequent blog post last year covered two concrete real-world examples of Graph from our codebase: composing production services, and generating personalized newsfeeds in real time.

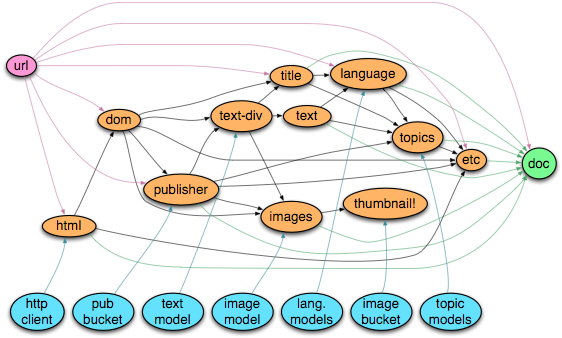

We’ll be discussing these applications more in later posts, once we get a chance to open-source more of the infrastructure built on top of Graph that supports them. Today, we want to focus on yet another application: our streaming document processing pipeline, or ‘doc’ Graph:

The doc Graph

As you can see, the doc Graph starts with an input URL (at left), and performs a sequence of interrelated steps to fetch HTML, parse HTML into a DOM structure, then extract the ‘article’ (main) text div, figure out its publisher, best images, title, and text, write image thumbnails to s3, infer a document language and topics, and so on. The results of these analyses are then collected into a final doc at right, which is then shipped onwards to another service for further analysis, indexing, and ultimately presentation to our users.

In addition to the URL input, many of the nodes in this Graph take additional static resources (in blue), such as S3 buckets or machine learning models for extracting article text, high-quality images, or article topics. At any given time, a single instance of our doc-fetcher service may be concurrently executing hundreds of copies of this Graph on different URLs (but with these same static resources).

The actual specification and use of the doc Graph looks like this:

where resource-map is a map of resources {:http-client … :pub-bucket … …}, and the compiled url->doc fn is then mapped over a stream of URLs using a thread pool.

Graph and complexity overhead

Now, we can examine the kinds of complexity overhead that are avoided by using Graph, rather than writing a function such as url->doc manually as a monolithic composition of the same components.

Just the ‘what’

Complex computations like our doc processing pipeline can have many interdependent steps, and each step can have multiple parents, children, and auxiliary resources. If we directly wrote code for url->doc, we would have to concern ourselves with many incidental details about how data flows, such as:

-

how values are cached and saved between steps (i.e.,

publisherandtext-divcan share the samedom), -

how resources are passed into

url->docand then routed to the appropriate node functions, and -

the precise order in which the steps should be executed.

The doc Graph sidesteps all of this complexity overhead, simply stating what the node functions are and what inputs they take. Then, a generic ‘Graph compiler’ (a fancy name a 20-line function) takes care of all the remaining details, including deciding how the steps should be ordered, caching of intermediate values, and executing each step function with the proper arguments (or throwing an error if the Graph is malformed). Moreover, various compilers can implement these choices differently, including cool tricks like auto-parallelization of independent steps (e.g., text and images) that would be a major source of additional complexity for a manual implementer.

Supporting related use cases

Sometimes we want to run different variants or subsets of a general type of computation. For instance, when a new user joins, we generate topic suggestions from Twitter shares by extracting topics from linked URLs. This is the same complex computation carried out by a portion of our normal document processing pipeline, but in this case we don’t care about other steps such as extracting the best image. These topic suggestions must be fast – we need to run them over hundreds of URLs in just seconds — so we’d like to avoid doing any unnecessary work (e.g., image extraction and thumbnail generation). But manually refactoring a hand-written url->doc function to support this url->topics and related use-cases would lead to a huge mess of complexity overhead (often involving a copy-paste job).

With Graph, however, we get such related uses cases for free. Since a Graph only describes the structure of a computation without committing to unnecessary details about which steps are actually executed and when, it’s trivial to just run a portion of a Graph (e.g., topics and its ancestors) and skip the rest of the nodes. We can also just use the built-in graph/lazy-compile compiler to generate a version of url->doc that returns a doc where fields are computed on demand, and unused results have almost no additional cost.

Introspection and Monitoring

In addition to maintaining the code corresponding to complex computations, we also need to make sure this code is properly documented and the documentation is kept up-to-date. Part of this documentation often includes an image describing the steps and their relationships (like the one shown above for the doc Graph). With Graph, this again comes for free – images like the above can be automatically generated from a Graph definition, with no manual intervention.

When putting complex systems into production, we also need to monitor them to collect statistics about how they’re working – for instance, how often each step function is called, how long it takes, what exceptions are thrown within it, and so on. Manually instrumenting a complex computation typically involves wrapping each step in monitoring code, which adds complexity overhead and makes it more difficult to understand the structure of the computation that we actually care about. In contrast, instrumenting a Graph just involves calling a higher-order function on the Graph that wraps each step in monitoring code (the future-graph/observe function above), without modifying and cluttering up the code describing the core computation.

Similarly, higher-order operations on Graphs make it easy to modify, extend, compose, and test them in new and powerful ways, which will be the subjects of future posts.

Graph and beyond

We hope you’ll go check out Graph, and let us know what you think. While you’re browsing the code, we also recommend checking out some other supporting namespaces in the project, especially plumbing.core which is a library of our very favorite Clojure utility functions. We’d love to hear comments, suggestions, and details about use cases you dream up.

Please let us know what you think in the Hacker News thread.