How We Manage the Android Client App State

Application State on Android

We’ve written about managing user data maintained within the memory of the application (a.k.a. “app state”) in the past. In this post, we talk about some of the challenges we faced when managing state in our recently released Android app. For performance and tooling reasons, we decided to write a native Java app. This meant we had to face the challenges of managing app state in a new and unfamiliar context: the Android Application Framework. Our solution manages app state in a clean and modular way that coexists in harmony with the Android activity lifecycle.

Keeping a cached version of backend state is particularly important when developing mobile apps because the network connection has a high latency and is often flaky. But, keeping local state also adds the complexity of ensuring it is consistent across the app. We hope to convey some of the lessons we learned about the activity lifecycle and the tradeoffs of different approaches to managing app state within the Android Application Framework.

Example

To help explain the notion of app state, let’s see an example. The app allows users to follow topics to receive recommended content based on the topics they follow. For example, Brad may follow the topic “Cats” in order to see recommended content about “Cats”. The ground truth of whether or not Brad is following “Cats” is maintained on the backend. So the backend is in exactly one of the following two states either:

1. Brad Follows Cats

or

2. Brad does not follow Cats

The client application is the interface through which users access and update these values on the backend servers. For Brad, the client application allows him to update this topic-user follow state on the server by following or unfollowing “Cats”. The client app also renders this state in various places where the topic surfaces:

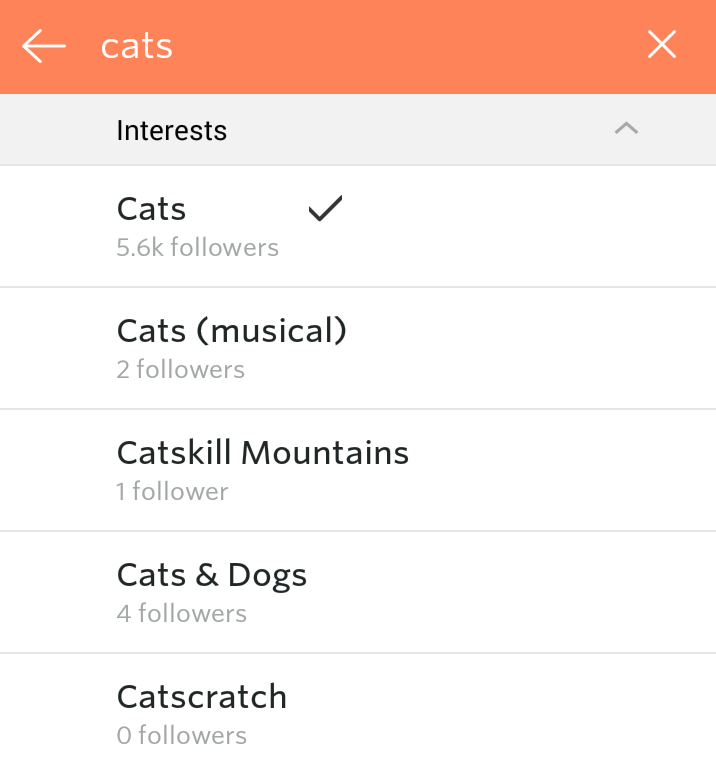

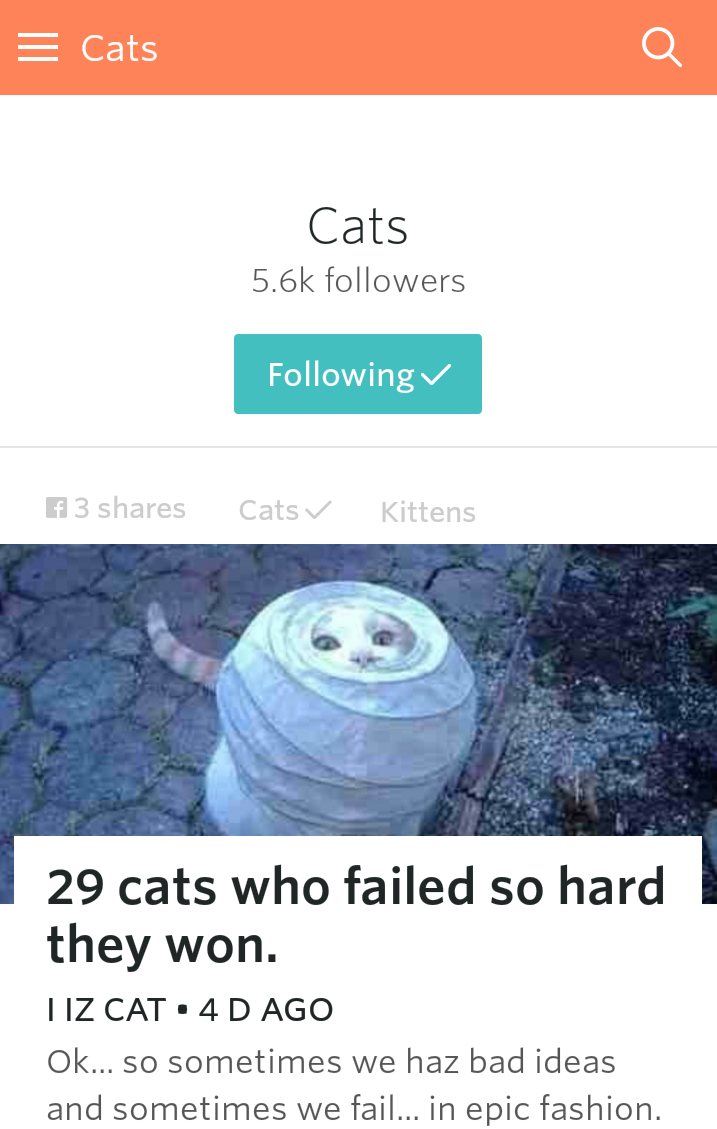

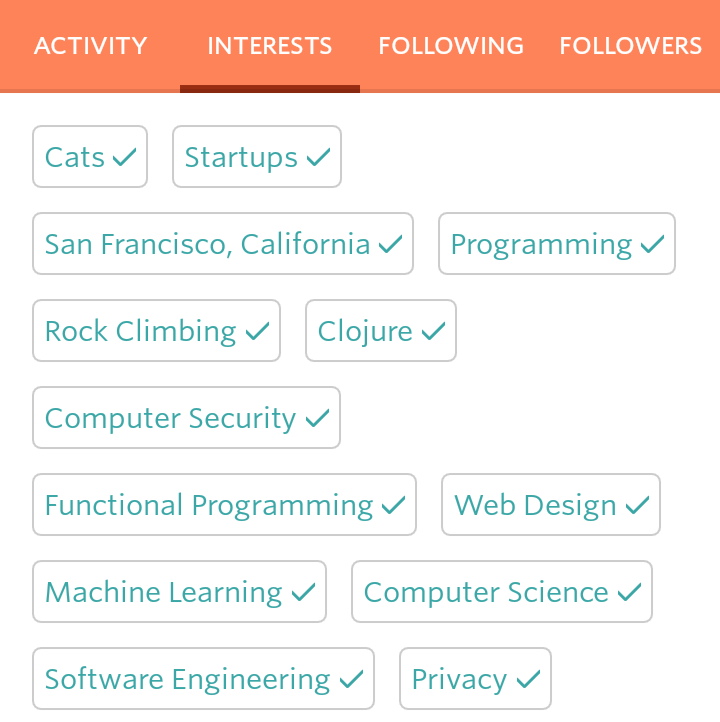

| Search | Header of Cats Topic | Topics Lists |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The main challenge of managing app state on the client is ensuring that these different representations are consistent and up-to-date with the backend. Put another way, something has gone wrong if our user, Brad, simultaneously sees two conflicting representations: one that says that he is following “Cats” and one that says he is not, which leads to confusion and a poor user experience. We also want the representation of this state on the client to be dynamic: if Brad decides to unfollow “Cats,” we want the many places where this state is rendered to be updated. Hence, we need a way to represent this topic-user follow state in the application in a way that allows it to render consistently and be dynamically updated.

Solution 1: Caching App State Across Activities

In mobile apps, where the network connection is often flaky and high-latency, it is important to cache network responses. The first approach we will consider is keeping a client-side cache on each screen and passing the cache between screens.

Before we get specific about the implementation, let’s review some basics of the Android Application Framework. Each “screen” in the framework is represented in code as an instance of the Activity class. For example, the images above show several examples of activities in the app: an activity containing the user’s list of currently followed topics, an activity for the “Cats” topic feed, and the search activity. Each one of these activities needs to know about the topic-user follow state.

To implement our caching solution, we can send one network request upfront for the set of followed topics from the onCreate method of the Main Activity (the first activity that the android OS launches in the app). Throughout the course of the app’s lifetime, each activity may start up subsequent activities as the user transitions between different screens, and can pass app state to subsequent activities using Intents. In pseudocode, the solution might look roughly like:

We would repeat this code in each activity that needs to reference the topic-user follow state. By saving the state in an instance variable, each activity can just look it up in the followState map, avoiding a network request for information already present on the client.

Unfortunately, this solution suffers from a couple of problems, the first of which is cluttered code. In order to implement this solution, we must always remember to pass along the topic-user follow state whenever we start a new activity. Otherwise, the downstream activity will not have the state it needs, and will have to fetch it from the server (adding logic to check whether we have the state locally or have to fetch it over the network adds even more code clutter and complexity). We might try to optimize the code to avoid passing the state to activities that do not directly reference it; however, we run the risk of breaking the chain for downstream activities that do reference the state. User-topic follow state is just one of the pieces of user state; as the number of pieces of cached state grows, so does the code bloat.

The second problem with this solution is that as users navigate between activities, the state is serialized and deserialized, effectively creating duplicate representations of the same state, which may fall out of sync. For example, consider a situation where the user has just completed a search on the SearchActivity and then navigates to the “Cats” TopicFeedActivity. On the topic feed, the user follows the “Cats” topic and then presses “back” to return to the SearchActivity. Now, because the search results were rendered from an older copy of the state, the screen will incorrectly show that the user is not following “Cats.” With this solution, we would have to ensure the new information is communicated back to the copy of the app state in older activities and have them re-render with the updated state.

Solution 2: Global App State

The distributed app state in Solution 1 introduced code bloat from needing to communicate the app state between activities and possible cache inconsistencies from having multiple copies of the same state that could easily fall out of sync. Both of these problems can be addressed by using a single representation of the app state that is referenced from all the activities that need it.

This approach is commonly implemented with the Singleton pattern, which is embraced by many Android developers. In our app, we have a singleton called the TopicManager that maintains the follow state for each topic and provides methods for querying it and updating it throughout the app.

We use the excellent annotations provided by the Dagger library to inject the singleton instance of the TopicManager into all the places that need it. For example, in the SearchActivity, we request that Dagger inject TopicManager like so:

and then to render each topic in the list of search results, we can query the TopicManager for whether the topic is currently followed:

With this solution, each activity independently requests only the pieces of cached app state that it needs. By no longer requiring each activity to pass the state downstream to the next activity, we reduce the code coupling that forms an easily broken chain.

Responding to State Updates

Whenever the state changes, we still need to update all the places that render it. Within our app, we broadcast notifications of state transitions via messages along an event bus (we’re using the fantastic Otto library as our elegant and lightweight event bus). Whenever the user-topic follow state is updated, the TopicManager fires an event on the bus:

All interested parties subscribe to the these events, and when a TopicUpdateEvent arrives along the bus, the places in the app that render the state can update themselves. As a general rule, the update code is shared with the initial rendering code. For example, for the SearchActivity, the update code just calls the notifyDataSetChanged() which triggers the adapter backing the list of activities to intelligently re-render itself and update the visible UI components that have changed. The complete, unabridged code to trigger the UI update is simply:

The call to notifyDataSetChanged() triggers the getView() method from above to run and update the UI.

Note that the activities on the backstack that also represent the state are unsubscribed from the event bus, and thus do not receive the notifications that the state has updated. Fortunately, it is easy to keep these backgrounded activities up-to-date because they will rerun the render code when they resume. Thanks to caching the app state, this re-rendering is fast.

Saving Instance State within the Android Activity Lifecycle

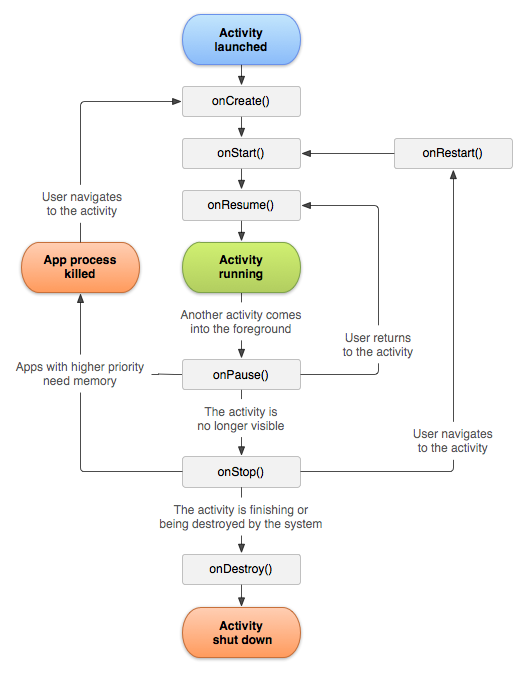

Keeping the cached state within a separate singleton class works harmoniously with the Android activity lifecycle.

| Android Activity Lifecycle |

|---|

|

In the Android Application Framework, each activity has its own set of lifecycle methods that are run when the user transitions between activities or triggers a configuration change such as rotating the device between portrait and landscape mode. For example, when the user rotates the device, the current activity is paused, stopped, and destroyed, a new instance of the Activity class is constructed, and then the onCreate, onStart, and onResume methods are called on the new instance. It is an unfortunate fact of the Android activity lifecycle that the values assigned to instance variables in the old activity object do not automatically carry over into the new activity. Instead, all instance variables must be re-initialized in the new activity object. In our experience, improper initialization of instance variables is the source of most null pointer exceptions.

The singleton holding the client-side cache is a separate object that exists independent of any activity. Because it lives outside the Android activity lifecycle, it does not get destroyed when a particular activity undergoes a configuration change. The Dagger library automatically ensures that the ApplicationContext maintains a reference to each global singleton to ensure that it is not garbage collected. Activities that reference these singletons typically inject them into instance variables in the onCreate() method, and so do not need devote special attention to making sure they are saved in the old activity object and restored in the new one. By sidestepping the need for explicitly saving and restoring instance state, we reduce the amount of error-prone bookkeeping needed in more distributed forms of client-side caching (e.g. the activity-level caching in Solution 1).

Global App State Under Pressure

We released a beta version of the app that made heavy use of our global singleton abstraction. After a day in the wild, we started seeing many null pointer related crashes from many different parts of the app, which we couldn’t reproduce. Eventually, we came across a post on stackoverflow saying that Android can kill a backgrounded app to free memory. By default, instance variables are not persisted when Android kills the app. Unintuitively, when the user switches back to a killed app, the Android OS restarts the app directly in the last activity with focus, skipping over the MainActivity which initializes the instance variables in the global singletons. Any instance variables in the global singletons that are set by the MainActivity will be null. By using ADB to kill the backgrounded app, we reproduced the problem – confirming the root cause of the crashes.

Intelligently Persisting Global App State

We considered many solutions to address the null pointer problems that result when Android kills the app in the backgrounded state. For example, we considered lazily initializing the instance variables with a request to the backend. Unfortunately, this approach would require refactoring most of the codebase. An alternative solution that we considered was writing all updates to the app state to persistent storage, such as a file or database. We discarded this idea because it would introduce too much complexity for keeping the in-memory representation in sync with the persisted version and in dealing with stale versions of the persisted state.

Fortunately, the Android framework provides a mechanism for saving and restoring instance state for activities. When the Android framework is going to stop an activity, for example when there is a configuration change, it first calls the onSaveInstanceState method and passes it a Bundle (essentially a map from keys to arbitrary objects) in which the activity can save any instance variables that it wants to be available when the activity is recreated. This Bundle with all the saved state is passed as an argument to the onCreate method of the new activity, which can lookup the values of the instance variables persisted when onSaveInstanceState was called. This save instance state mechanism for activities provides a nice hook for ensuring that all instance variables are initialized when the activity is recreated. We understood this mechanism to be the preferred way for saving instance state on Android, and we just needed to figure out a way to use it for saving the state of our global singletons.

The way we saved global singletons in the activity’s instance state bundle is with a StateSaver class that has a handle to each of the global singletons that maintain instance state.

The StateSaver provides its own saveInstanceState method that takes a Bundle into which instance state can be persisted. We also modified each of the global singletons to have their own saveInstanceState and restoreInstanceState methods which the StateSaver calls to provide them a hook to save and restore their state. This StateSaver is a single class that must be injected into every activity and provides a hook for the activity to save the state of the global singletons whenever it is minimized. We effectively are piggy-backing on the activity-level saveInstanceState by using it to also save the global app state for all of the global singletons. We avoided code bloat by subclassing activity to StateSavingActivity and overriding the onSaveInstanceState and onCreate methods to save and restore the StateSaver; we replaced each activity in our app with an instance of the StateSavingActivity. While it does involve refactoring to StateSavingActivitys, we felt the StateSaver solution was better than the alternatives.

Summary

There are many options for managing state on the client. Each approach comes with its own tradeoffs. For our Android mobile app, where the network connection can be flaky, we found that maintaining several global cache objects (aka “managers”) keeps things modular and DRY. By leveraging some great open source libraries (Dagger and Otto), the manager solution is easy to implement and adopt across those activities in the app that need to access state. Our approach plays well with the Android Application Framework, and doesn’t create new serialized data formats that need to be cleaned up when upgrading the app. We’re just getting started developing in the Android space and are curious to hear your war stories and best practices.